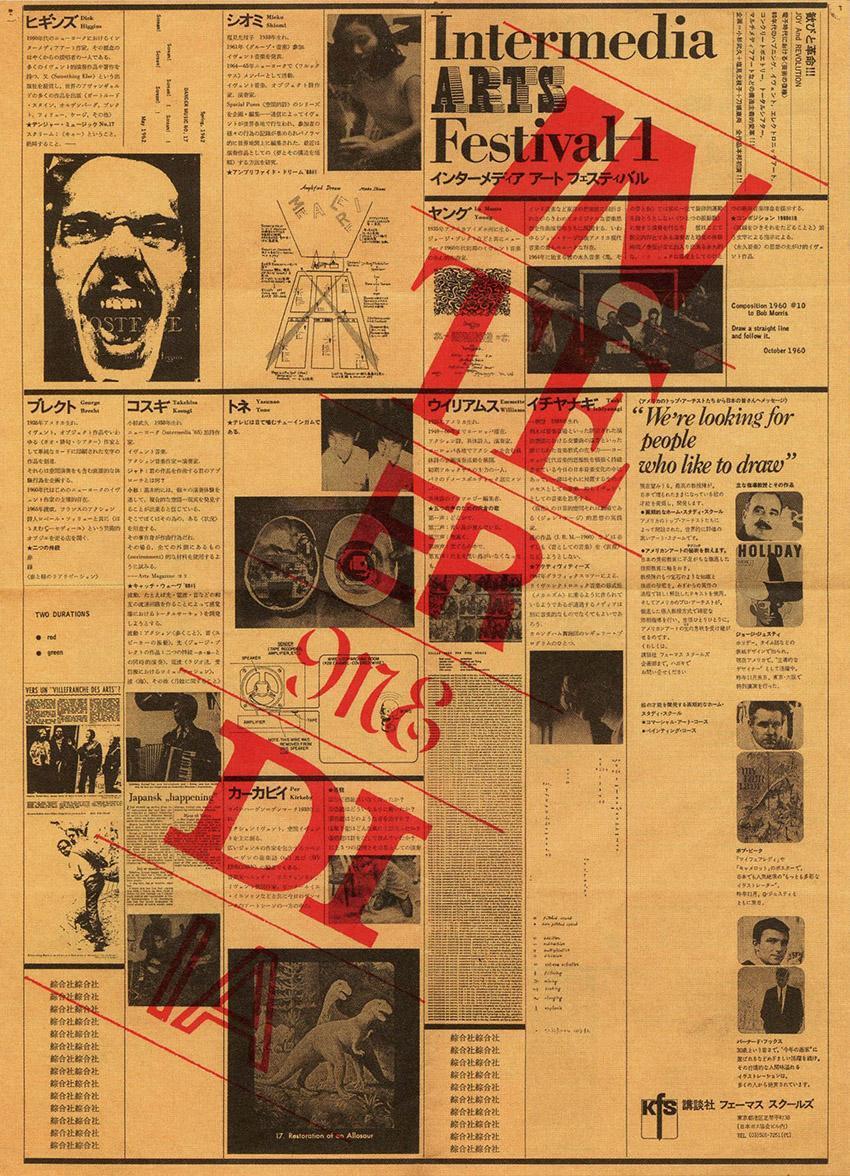

Intermedia and Expanded Cinema, both as critical approach and artistic practice, left an indelible mark in a period of Japanese art history that is broadly considered to be one of its most dynamic moments in the wake of its postwar reemergence.

Despite the burgeoning interest in academic and curatorial circles in this segment of Japanese art history, the paucity of readily available material in a language other that Japanese has meant the local context, particularly the ways in which the terms were critically debated, was relatively neglected.

Rather than assuming the interpretations of the terms were the same as their counterparts abroad, we decided to commission translations of a selection of key texts that we felt were instrumental in shaping the specific discourse around these terms.

Through these translations, our hope is that Japanese debates on intermedia can contribute to international discourse, and that works of Japanese Expanded cinema can be preserved, reenacted and analyzed with these discussions in mind.

Collaborative Cataloging Japan is an international non-profit, 501(c)3, organization dedicated to preserving the legacy of Japanese experimental moving image produced from the 1950s through 1980s, including fine art on film and video, documentations of performance, independently produced documentaries, experimental animation and experimental television.

www.collabjapan.org

Read the full version of Julian Ross introductory essay

Situating Intermedia and Expanded Cinema in 1960s Japan.

“Two prints of the same film are projected simultaneously and on top of one another. A few seconds delay separates the overlapping images, the resulting effect being one image appears as a ghost of the other, chasing its counterpart but never quite reaching it. Onscreen, a point-of-view perspective gives a gliding tour of a familiar city with its inhabitants occasionally joining in with on-street performances and happenings. Back at the site of projection, the artist, standing next to the 16mm projectors, is holding up several colored gels to give different color tones to the black-and-white images. As the projection takes place across approximately forty minutes, the artist introduces increasing numbers of colors, blocks the light with his hands, and alternates these interruptions against the light between the two projectors.

A digital clock, with the time out of sync between the two projectors, fills the frame for the last few minutes until the two projectors run out of film one after the other.

What I describe here is what an audience might have seen on the first occasion that Phenomenology of Zeitgeist (Jidai seishin no genshōgaku, 1967), a performance with two analogue film projectors, was presented to the public in Jiyū gekijō in Tokyo, as part of their event series The Underground in March (Sangatsu no angura) in March 1967. Sandwiched between the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo and the 1970 World Exposition in Osaka, 1967 in Japan marks a period of economic ascendance years after their defeat against the Allied forces in World War II. Political unrest is on the rise as the re-signing of the Anpo US-Japan Security Treaty approaches: scheduled for 1970, this event is set to occur in a moment when American military forces are in Vietnam, universities have been exposed for their misappropriation of money, and farmers are being forcibly ejected from their land to build what will become Narita airport…”